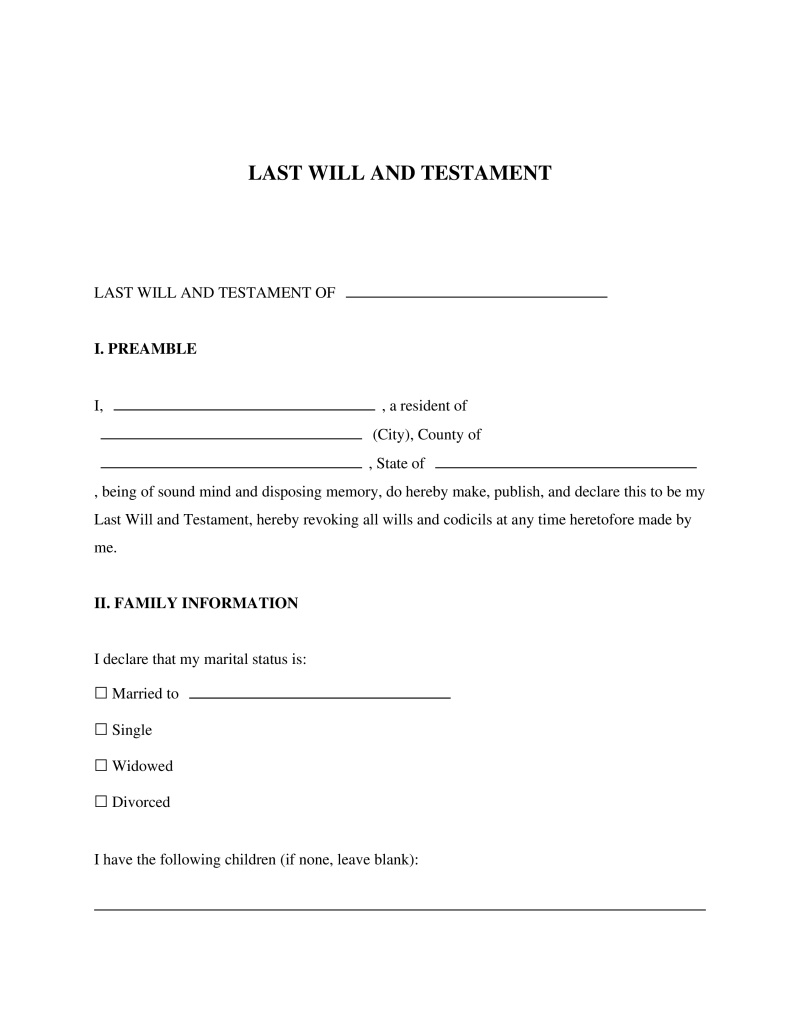

A Last Will and Testament is a legal document that specifies how an individual's assets and property should be distributed after death.

Testator Over 18

Most states require the Testator to be at least 18 years old to make a valid Will.

Table of Contents

What is a Last Will and Testament?

A Last Will and Testament is a formal legal document that articulates a person's final wishes regarding the distribution of their assets and the care of any minor dependents after their death. This instrument serves as the primary method for an individual, known as the testator, to designate an executor who will manage the estate and ensure that property is transferred to the intended beneficiaries. While often associated with the wealthy or elderly, this document is utilized by adults of all ages and economic backgrounds to prevent state-intervention in asset distribution and to provide clear instructions regarding guardianship of children.

Historical Overview and Legal Definition

The concept of the will dates back to ancient Roman law, which introduced the ability for a citizen to direct the disposition of their property after death. In the common law tradition, the distinction was historically made between a "will," which disposed of real property (land), and a "testament," which disposed of personal property. Over time, these concepts merged into the singular legal instrument known today. The primary purpose of the document is to exercise testamentary freedom, allowing the owner of property to decide its fate rather than having it distributed according to the default rules of intestacy.

In modern jurisprudence, understanding what is a last will and testament involves recognizing it as an ambulatory document. This means it has no legal effect until the moment of the testator's death and can be revoked, amended, or replaced at any time while the testator remains mentally competent. The document guides the probate court, providing the blueprint for the settlement of the estate, payment of debts, and transfer of wealth.

Types of Testamentary Documents

There are several variations of wills recognized by different jurisdictions, each serving specific needs or circumstances. Understanding these distinctions is vital when determining how to make a last will and testament that suits a specific situation.

Simple Will

A simple will is the most common form, used to distribute assets in a straightforward manner. It typically lists the beneficiaries, designates a guardian for minor children, and appoints an executor. This format is generally sufficient for individuals with uncomplicated estates.

Joint and Mutual Wills

Joint wills are one document signed by two people, usually spouses, leaving everything to the survivor. Mutual wills are separate documents with reciprocal provisions. Individuals often search for a free last will and testament template for married couple when attempting to draft these documents without legal counsel. However, it is important to note that joint wills can create binding contracts that may prevent the surviving spouse from changing the distribution plan after the first spouse dies, a rigidity that leads many legal professionals to recommend separate reciprocal wills instead.

Holographic Will

A holographic will is a document written entirely in the handwriting of the testator and signed by them. It generally does not require witnesses. However, not all states recognize holographic wills, and those that do often impose strict requirements to prove the handwriting is authentic.

Nuncupative Will

Often called a "deathbed will," this is an oral will spoken by the testator before witnesses. These are rarely recognized and are typically limited to personal property of low value or specific circumstances, such as soldiers in active military service.

Required Elements of a Valid Last Will and Testament

For a will to be legally binding, it must meet specific criteria established by state law. While variations exist, the following elements are universally critical for validity.

- Testamentary Capacity: The testator must be of sound mind, understanding the nature of their assets and the consequences of the document.

- Testamentary Intent: The language used must clearly demonstrate the intent to transfer property upon death, not merely express a wish or hope.

- Identification of Beneficiaries: The document must clearly identify who is to receive the assets, whether they are individuals, charities, or trusts.

- Appointment of Executor: A personal representative must be named to carry out the instructions.

- Proper Execution: The document must be signed and witnessed according to state statutes.

How to Complete a Last Will and Testament

The process of establishing a will involves several methodical steps to ensure the document accurately reflects the testator's wishes and holds up in court. Those researching how to write a last will and testament should follow this general procedure.

- Step 1: Inventory Assets and Debts – Before drafting, compile a comprehensive list of all significant assets, including real estate, bank accounts, investments, vehicles, and personal heirlooms, as well as outstanding debts.

- Step 2: Select Beneficiaries – Determine exactly who will inherit specific items or percentages of the residual estate. This includes naming contingent beneficiaries in case the primary beneficiaries predecease the testator.

- Step 3: Choose an Executor – Select a trustworthy individual to manage the probate process. It is advisable to ask the potential executor for permission before naming them in the document.

- Step 4: Designate Guardians – For parents of minor children, this is arguably the most critical step. Identify a primary and alternate guardian to assume legal custody.

- Step 5: Draft the Document – Create the document using clear, unambiguous language. While many use software or templates, the language must align with state laws.

- Step 6: Execute the Document – Sign the will in the presence of the required number of witnesses (usually two) who are not beneficiaries. Many states also recommend or require notarization to make the will "self-proving."

Legal Requirements and State Statutes

The validity of a Last Will and Testament is governed strictly by state law, although many states have adopted the Uniform Probate Code (UPC) to standardize the process. Under the UPC and most non-UPC state statutes, the testator must be at least 18 years of age and possess "sound mind." This legal standard, often referred to as testamentary capacity, requires that the individual understands the extent of their property, the natural objects of their bounty (family), and the nature of the disposition.

Federal laws generally do not govern the creation of wills, as probate is a state matter. However, federal tax laws, specifically the Internal Revenue Code, play a significant role in estate taxation for high-net-worth individuals. Additionally, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) overrides state will provisions regarding 401(k)s and certain pension plans; these assets pass directly to the named beneficiary on the plan document, regardless of what is written in the will.

Failure to comply with specific state formalities can result in the will being declared void. For example, under the statutes of states like Florida or New York, the witnesses must sign in the presence of the testator and often in the presence of each other. If a will is declared invalid, the estate is treated as if the deceased died "intestate," meaning the state's default laws determine who inherits the property, typically prioritizing spouses and children, then parents and siblings. This statutory distribution may be completely contrary to the deceased's actual wishes.

Revocation and Amendment

A will is not a permanent document until the testator dies. It can be changed or revoked at any time, provided the testator retains mental competence. There are three primary ways to revoke a will: by physical destruction (burning, tearing, or shredding with the intent to revoke), by creating a new will that explicitly revokes prior ones, or by operation of law (such as divorce, which in many states automatically revokes provisions favoring the ex-spouse).

To make minor changes without rewriting the entire document, a testator may use a legal amendment known as a codicil. A codicil must be executed with the same legal formalities—signing and witnessing—as the original will. However, because codicils can create confusion or contradictions, modern legal practice often encourages drafting a completely new will rather than relying on multiple amendments.

FAQs

Do you have a question about a Last Will and Testament?

Example questions:

Not the form you're looking for?

Try our legal document generator to create a custom document

Community Discussion

Share your experience and help others

Legal Notice: Comments are personal opinions and do not constitute legal advice. Always consult a qualified attorney for matters specific to your situation.

Comments (0)

Leave a Comment

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!